Sunday’s elections in Germany are generally considered a serious blow to Chancellor Merkel’s stance on refugees. Her conservative party did not gain majorities in two states, and does have an easy government option in the other one. Meanwhile, the AfD, founded on the basis of criticism of her european policies and incorporating a growing anti-refugee sentiment, entered all three state legislatures with 12 to 24 percent of the vote. However, despite both AfD and Merkel’s CDU being on the right wing of politics, they are not the main competitors in this political shakeup.

The conservative CDU is not doing much worse than 2011

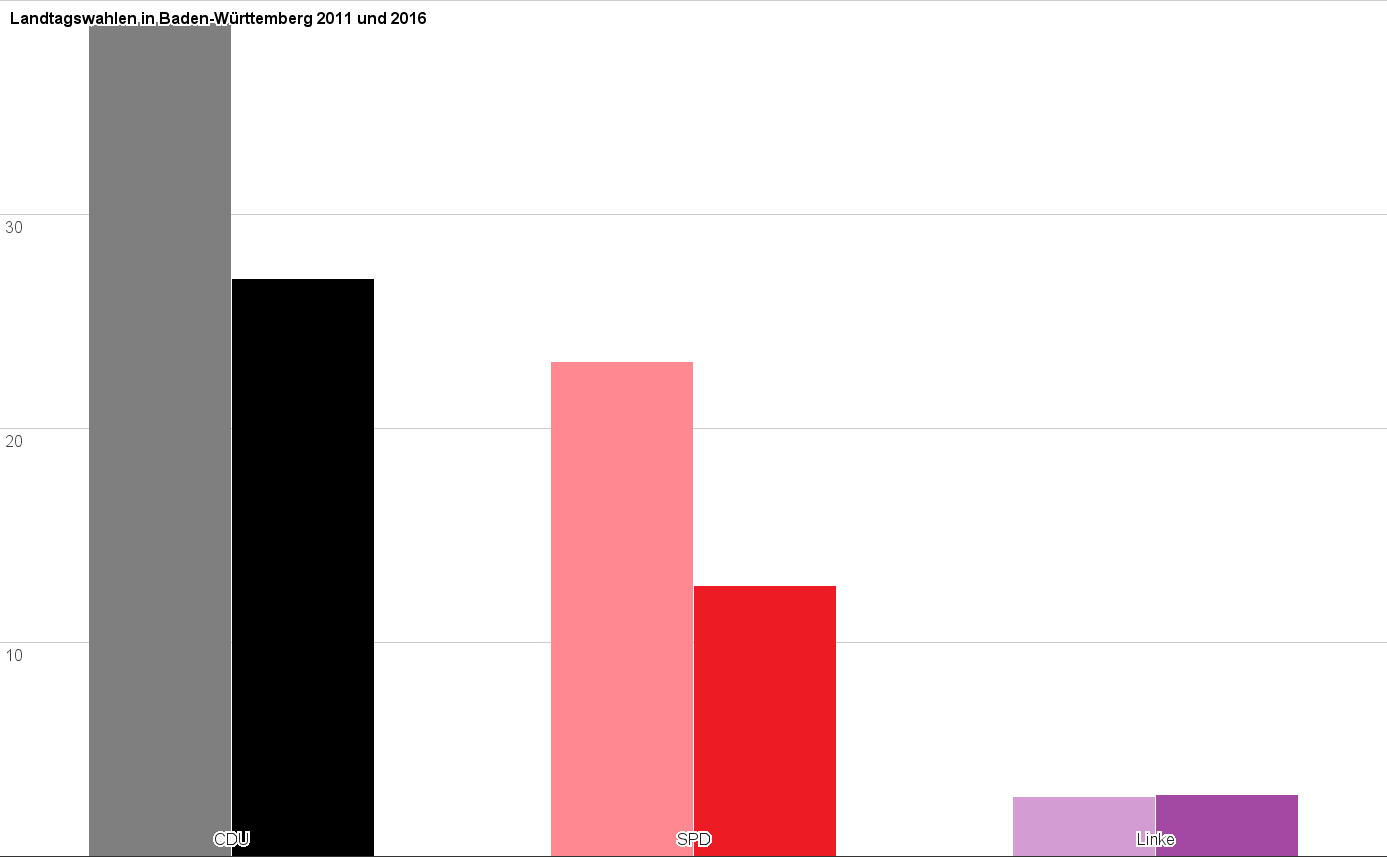

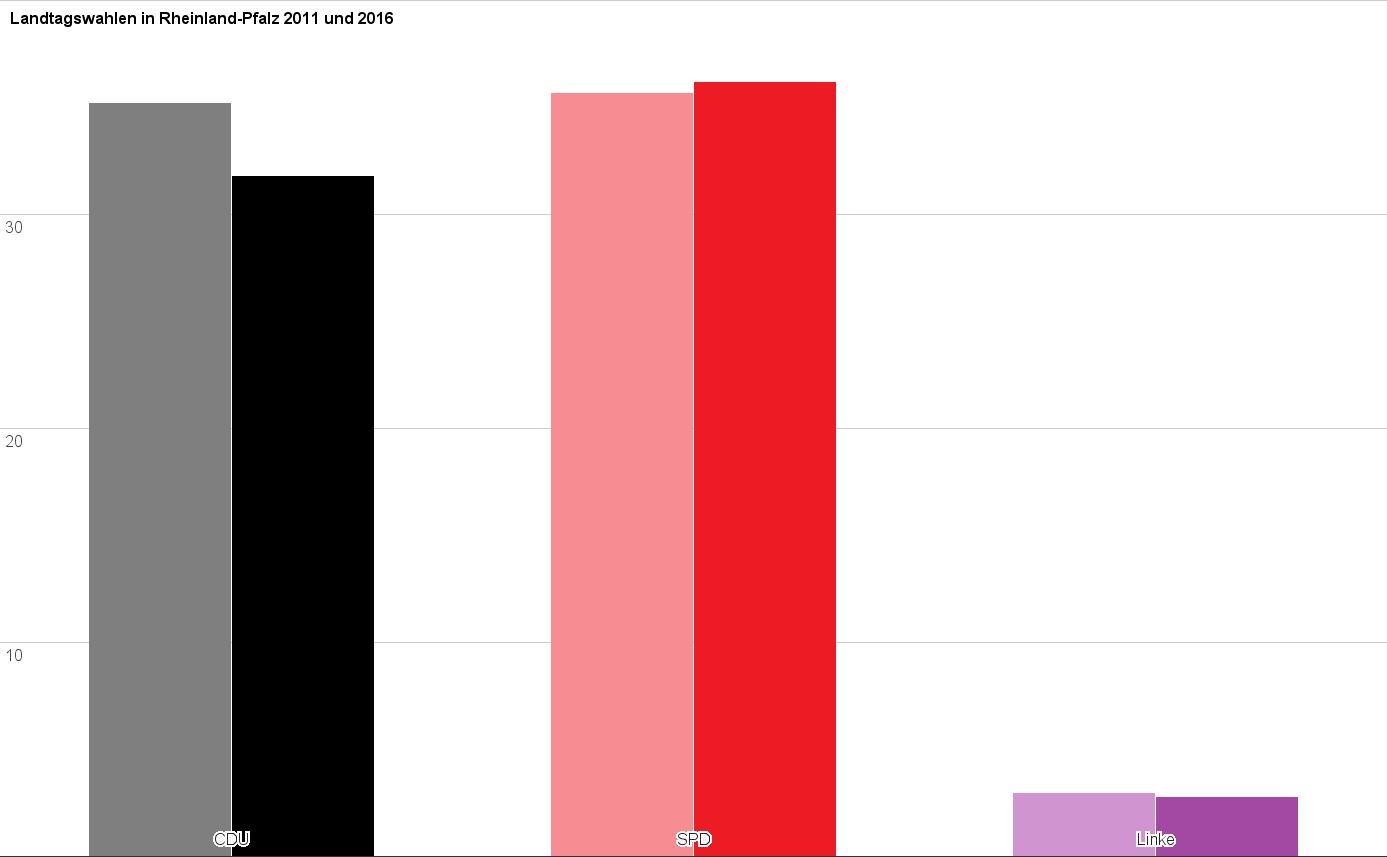

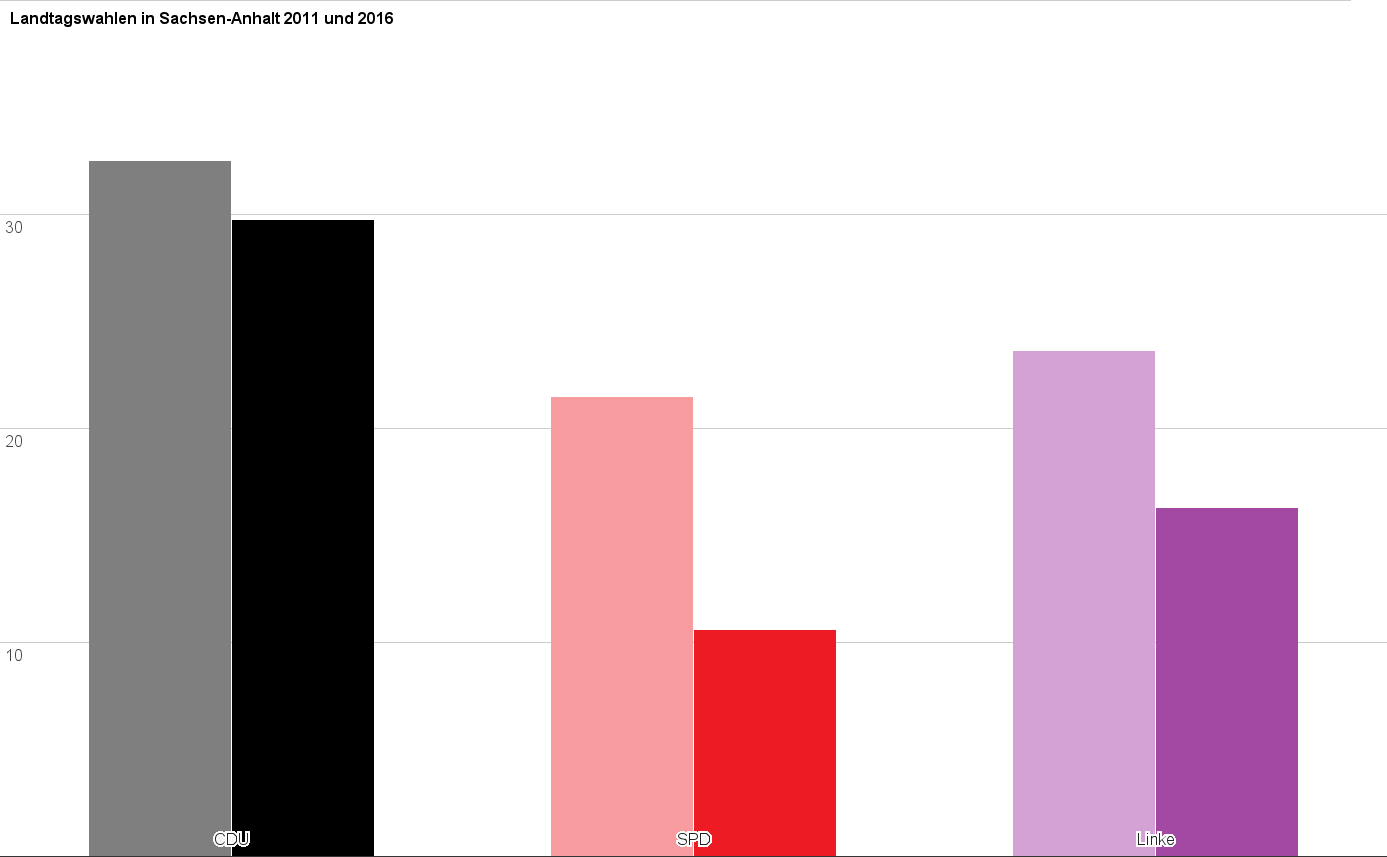

With the political framing, it is easy to forget where the parties were coming from. In 2011, the CDU was already performing quite poorly, against an already weakened social-democratic party (SPD). The resulting governments where coalitions between Greens and the SPD, led by SPD (Rhineland-Palatine) and Greens (Baden-Württemberg), respectively. Only in Saxony-Anhalt did the CDU become both the largest party and the ruling party in a not-so-big coalition with the SPD. Compared to that, the recent results are no big change: They will probably still head the government in Saxony-Anhalt. They might even enter coalitions in Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatine due to the unstable majorities otherwise available – their situation almost seems improved.

Meanwhile, the political left is doing poorly; the SPD is reduced to barely above 10 percent in two states, despite their win in Rhineland-Palatine, and the leftwing party “Linkspartei” did not make it into two legislatures at all, while losing a significant share of votes in Saxony-Anhalt. Apparently, in all three states, the AfD managed to gain votes from all major parties in relatively similar proportions (see here, here and here). Despite an ideological proximity to the conservative party, they also managed to pick up voters from center-left and far-left parties, as well as major gains amongst non-voters.

Their constituency consists of core-demographics of the political left

Other analysis show that in all three states, the AfD scored best amongst male voters with a medium to lower education who were either unemployed or blue-collar workers and somewhere between 25 and 44 years old.

Does that sound like core-demographics for the CDU? It sounds like groups that a) tend to vote less, and b) have interests that are represented by leftwing parties more than by right-wing parties. Groups benefitting from a strong welfare state, you would assume, are more likely to vote for parties that promote a welfare state, rather than a radically anti-welfare party like the AfD.

And this did indeed work in previous elections; when the Harz 4 reforms, initiated by a center-left government headed by the SPD were enacted, it gave rise to the Linkspartei and mobilized workers and unemployed alike to vote for them. Areas with a lot of poverty, as well as areas in Eastern Germany (where the party retains strong structures), have been the Linkspartei’s stronghold. And now, these are the areas where the AfD is performing extremely good – a threat much more for them than the CDU, whose generally older and better off electorate seems to overlap less with the AfD.

Opposition parties have better chances with swing voters

Another variable making predictions in European and German elections harder is the growing number of non-affiliated voters, who decide very late on a party. Protest votes are often easier to gain as an opposition party, as dissatisfaction with the government benefits their antagonists; additionally, big coalitions benefit the smaller parties disproportionately. The FDP rode this wave in 2009 when they almost doubled their voter share in federal elections and entered a coalition (only to get kicked out of parliament four years later), and the Linkspartei benefitted from this in 2005 and, to a smaller extent, in 2009. However, the current opposition seems incapable of benefitting from any weakness in the ruling parties; partly, because they have a hard time presenting themselves as a true alternative. Big coalitions are coalitions of compromise; on both fringes of government, the main criticism of such a government should be “this is not going far enough”.

But two factors are benefitting the AfD. First, unlike in 2005, there is no right-wing alternative to the government present in the federal legislature, as the FDP is not represented and the opposition consists of Greens and Linkspartei. But, even more devastating: The Left has a hard time scoring points with the electorate on immigration. It is rare for major leftwing parties to garner any support with pro-immigration stances, but very easy to alienate large groups of voters. Yes, Germany’s demographics are changing, but support for leftwing parties among people of color is high already and leaves little room for improvement; electoral success is generally based on a coalition with less immigration-friendly groups based on common economic interests. Therefore, an election focussing on social inequality is much easier for leftwing parties than an election accompanied by 600.000 refugees reaching Germany.

In other words: Even if Merkel would one day wake up and make a pivotal policy shift, it would not probably scratch the AfD. They strength is not only dependent on her policies, but rather on the inability of the Left to mobilize its core electorate: unemployed, workers and voters with lower levels of education. The French Front National has shown how a far-right party may mobilize workers and significantly weaken socialist parties – the AfD may be copying this. Already, senior leftists like Wagenknecht are attempting what some dub a nationalism from the left; SPD-frontrunner Gabriel’s attempt to talk to right-wing protesters may be interpreted this way as well. Alas: This may in turn alienate other supporters and start serious internal fights. Shifting the debate towards social issues seems a more promising approach, but right now, there does not seem to be a window to do this. And so, the AfD will continue to gain 10-15 percent of the vote until a new cleavage line in politics emerges that they cannot incorporate.