Since 2011, the Middle East has been shaken by democratic movements, backlashes against them and outright civil war. The relatively stable powers in the region, namely Iran, Saudi Arabia and Turkey, have been trying their best to benefit from the upheavals, intervening in various ways and getting embroiled in these conflicts. With one notable exception – Israel has been exceptionally hesitant to pursue any policy whatsoever towards the Arab spring.

In fact, even the term “Arab spring” has been contested in Israel, as it carries a distinctly positive notion – the term originated in the revolutions in 1848 as well as the Prague spring. But despite the revolutionaries’ optimism, shared by many Western observers (me included), policy makers in Israel have been more wary, pointing out the security issues for Israel and framing the movements towards that aspect.

These concerns are mirrored by Israeli policies. During the crisis in Egypt, Israel was more interested in getting a guarantee for peace by the Egyptian military than it was concerned about democracy, signalling support for the regime in contrast to its American and European allies, who seemed more keen on regime change. After all, when Mubarak was ousted, Israels worst nightmares seemed to come true: The Muslim Brotherhood, having close ties to Hamas, came to power. And even if they had not been clear supporters of the Hamas – the deteriorating state power under president Morsi seemed to spell out nothing good for Israel. A weaker government in Cairo would not be able to cooperate in Gaza, fight terrorism on the Sinai peninsula, and keep militants in its own borders in line.

Israeli spring vs Arab spring

Israel, or so it seems, had better things to do: In 2011, while Egyptians and Tunisians where revolting against their autocratic leaders, Israel saw a massive social movement, protesting against the deteriorating economic situation of the Middle and Lower classes. This provided Israeli leaders with a host of issues more pressing than democratic change in Arab countries. Add to that the coalition crisis in 2012, and Israel had a lot of reasons to focus domestically rather than create a major shift in its foreign policy. While Europe and America got involved in the Libyan and Syrian civil war, while Turkey’s and Qatar’s ambitions in Egypt failed, Netanyahu was busy maintaining power.

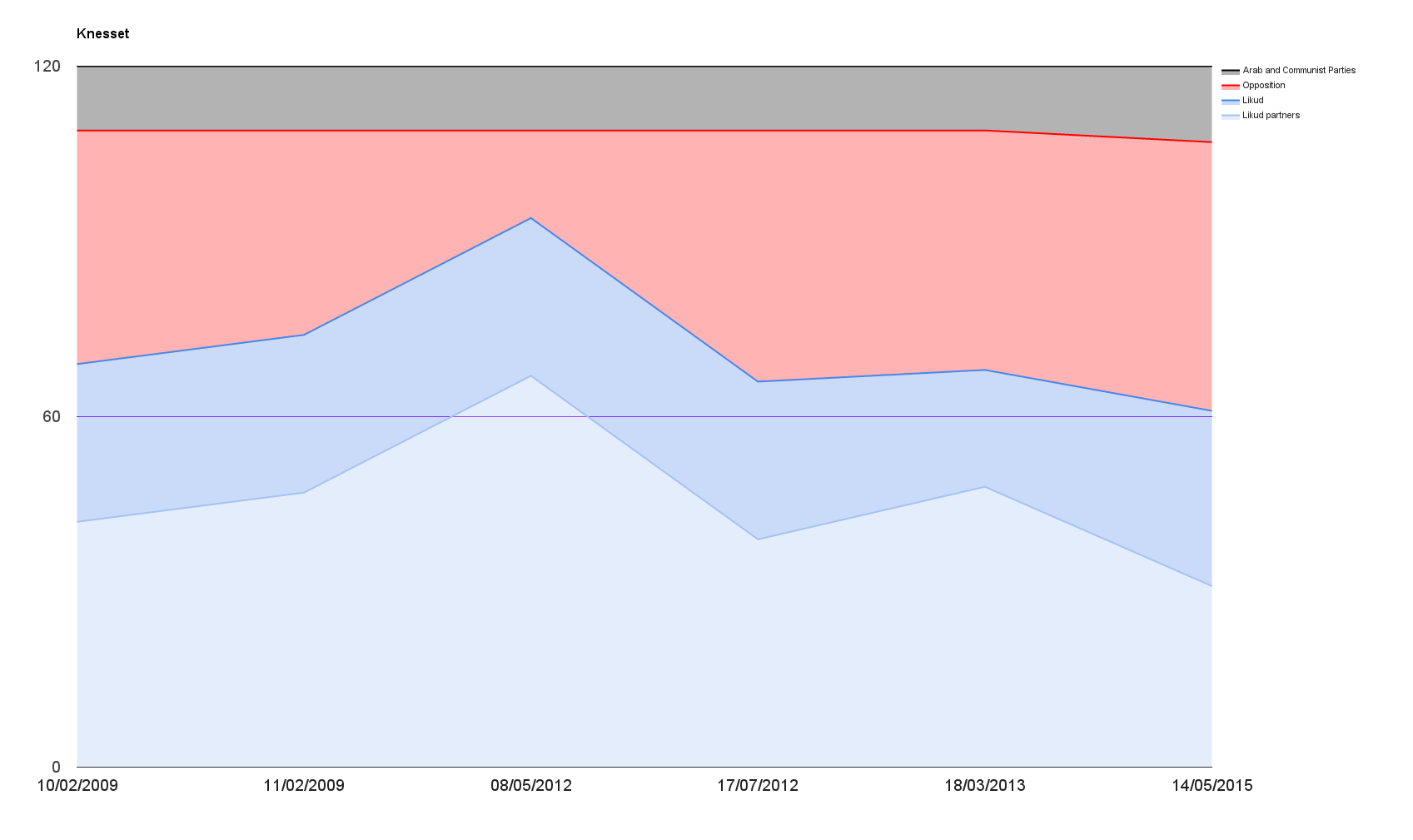

Simplifying the Israeli parliament for a graph is quite hard; with about a dozen parties in parliament, that split up and regrouped, continuity often exists through charismatic figures like Zivni, Atid, Liebermann and Netanyahu. In order to make it more assessable, I distinguish between Netanyahu, his coalition partners, opposition parties with viable chances of winning (who can be leftist, centrist or even right-wing), and Arab communists with whom no one in Israel’s mainstream would cooperate. The turmoil in 2012, where Netanyahu reshuffled his coalition, indicates the opposite of what he was hoping for: A weaker government, occupied with internal divisions and incapable of handling major issues like the peace process. Bibi can’t seem to lose elections; but that is more due to his skills in crafting coalitions that his electoral success.

Not intervening in these conflicts has kept Israel safe in many ways; it is not embroiled in the Syrian civil war, like Turkey, not threatened by spillover from Libya, like Egypt, and it had not alienated the Egyptian military like Turkey and Qatar have with their support for the Muslim Brotherhood. Their ties to key actors, in Syria and in Egypt, remain intact. The Arab spring even had some positive effects for Israel – diminished capabilities of the Syrian and Egyptian regimes increase relative military power of Israel. All its potential adversaries and competitors in the region, including Iran and Turkey, are busy dealing with other issues, like Isis.

Missing an opportunity

Israeli politicians seem baffled by the notion that they could have handled things differently. As a FES report points out, the Arab spring could provide opportunities for reconciliation and cooperation. Yet, Israel is faced with a publicity problem – if it supports democratic movements, it risks tarnishing the name of said movements by tying them to the “Zionist state”. If it supports autocratic regimes, it risks further deteriorating its own image by tying itself to autocrats.

A major factor in Arab-Israeli relations is the public image and Arab discourses about Israel. As long as there is no peace with Palestinians, this will likely continue; however, if the conflict would get solved, it would probably not abolish Israeli image issues. Anti-Israeli sentiment would likely persist. In democratic societies, with ties to Israeli civil society, this might change quicker – thus, creating democratic youth programmes like the EU, ideally in cooperation with the EU, would have created important links. Additionally, in a young democracy, politics can shift quickly; thus, supporting faction beneficial for Israel’s interest, the way Turkey and the Gulf States did, would have allowed Israel to create some sort of influence. Unlike Turkey, Israel could not rely on a close ideological ally like the Muslim Brotherhood; but providing help to the new democratic government would have opened up opportunities to set the tone. Rather than doing that, Israel chose to remain sidelined, in exchange for a promise by the Egyptian generals to maintain the peace deal.

Israel assumes it has small chances of influencing Arab domestic politics, and it fears a great security risks by Islamists ruling democratic countries. These fears, as understandable as they may be considering Hamas’ ties to the Muslim Brotherhood, can be put into perspective considering democratic peace theory. The notion that, under normal circumstances, full democracies do not fight wars against each other is one of the few stable assumptions in international relations. Considering this, military conflict between Israel and a democratic Arab government, now weakened by domestic strife and held responsible for warfare by an electorate, seems less likely.

If it had involved itself in the Arab spring, creating an actual policy, Israel could have gained a lot. Busy with domestic issues and fearful of repercussions, however, Israeli policy makers decided to sit this out. As a result, all they can hope for is a slightly different status quo. That status quo has been working in Israel’s favor so far; Tel Aviv should hope that doesn’t change any time soon.