2016 started off with Riyadh executing an influential Shia cleric, resulting in a massive diplomatic crisis with Iran. This is not the only risk taken by the Gulf monarchs recently, raising a question: Why is the monarchy, once so careful, now so proactive in their foreign policy?

In 2010, thanks to Wikileaks, we learned that Saudi-Arabia repeatedly urged the US to attack Iran. In 2011, Syria was shaken by the beginning of a civil war, with Gulf states quickly supporting the opposition against Iran-backed Asad. In the same year, Saudi-Arabia decided to increase oil production in order to combat rising prices due to the Arab Spring, and despite dropping oil prices, refused to decrease it again last year. Finally, last year, Saudi troops engages directly into the broiling Yemeni Civil War, going on and off since 2011 between a Saudi-backed government and Houthi insurgents, possibly backed by Iran.

Back in the days, during the Cold War, the Gulf states had it simple foreign policy wise. Follow the US to combat Soviet influence, keep oil prices stable, support Muslim states and foster cooperation amongst them, and maintain balance and stability. Iraq in the North had a strong army, Iran had its fleet, and both were competitors on the oil market, but luckily, they were busy keeping each other at bay.

The 21st century brought new challenges

But then, the Cold War ended, and the US was looking for new challenges, finding them in Iraq. When regime change occurred, it came with a price: There was no strong Iraq any more to keep Iran at bay, quite the opposite – there was a Shiite government, all too willing to cooperate with Iran, and worst of all: That government was unstable, ridden by civil war and conflict.

Riyadh had just started a new approach: Under pressure from its own population, it opted to not join the US invasion of Iraq and asked US troops to leave. No Saudi troops were involved in the aftermath of the US invasion. However, an unstable border presents its own challenged – insurgents, terrorists and criminals may pass it, and conflicts at the border may spill over.

The latter became a serious issue with the Arab Spring – suddenly, Arabs all over the Middle East were protesting their elites and demanding representation and social reforms. Saudi-Arabia did its best to contain those movements – it supported the Egyptian post-coup government not only symbolically, but, for example, by promising over 8 billion Dollars worth of investments.

Standing steady against the wind of change

First signs of conflict could be seen when Saudi-Arabia backed Bahrain’s Sunni monarchs against protests by their largely Shiite population, causing Iran to object strongly.

Even more dramatically, at least two of its neighbours where suddenly embroiled in bloody civil wars. In Syria, Asad, a close ally of Iran, was challenged by an opposition that seemed pro-Western and in favour of the Gulf states. In Yemen, within Saudi-Arabia’s traditional zone of influence, its allies were challenged by Houthi insurgents, who Riyadh claims to be supported by Iran (despite Teheran denying such allegations). Overall, the situation at Saudi-Arabia’s borders have dramatically deteriorated.

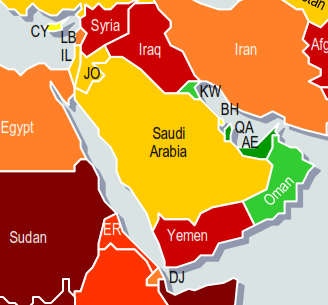

It’s neighbours have grown increasingly unstable over the last years. The recently published Fragile States Index’s map gives an idea about how the Middle East would look from a Saudi perspective (red indicates state weakness, green highlights stronger states).

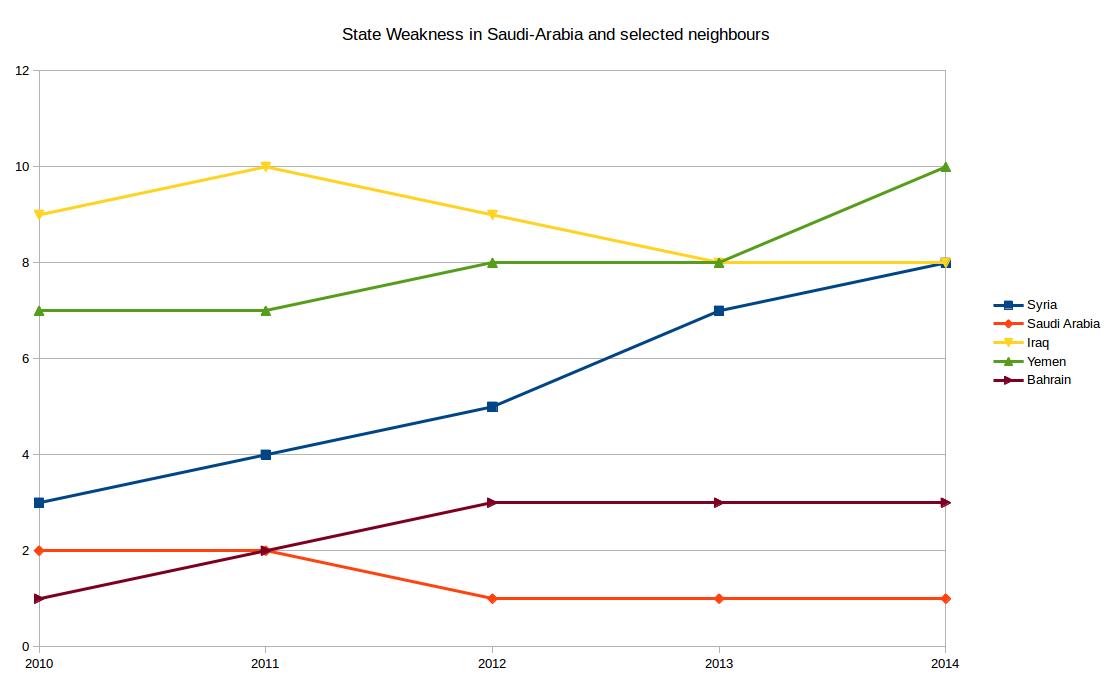

Monty G. Marshall and Benjamin R. Cole from the Center for Systemic Peace provide data on state fragility as well:

For this, I took their state fragility index, but left out the legitimacy indicators and only included their “effectiveness score” which covers political, security, economic and social effectiveness of states. I did this for all Saudi neighbours from 2010 to 2014, then dropped those that were independent actors, like UAE, Qatar, Jordan. I further dropped Oman and Kuwait due to their relative stability, and was left with Bahrain, Yemen, Iraq and Syria.

Surrounded by uncertainty, Saudi-Arabia needs to shape policy

Weak states have a couple of things in common. Their weakness creates insecurity for its neighbours; long border areas that are harder to control allow for contraband and people to cross over. Drugs, but also terrorists may enter Saudi-Arabia from either country, and thus challenge it. Salafists like ISIS (more active in Iraq and Syria) and Al Qaida (more active in Yemen) may gain support amongst Saudi nationals and thus pose even more of a domestic threat. As the largest country on the Arab peninsula, its borders are its weakness; Saudis may not rely on relative geographic protection, like UAE and Qatar may do, but has to actively secure its borders.

Weak states also have a certain open-endedness of their state structures. Where there are little structures, there is a lot to be shaped; involvement may secure states that are beneficial to intervening powers. Iraq, Syria and Yemen being embroiled in prolonged (military) conflicts over the nature of their states means that states like Saudi-Arabia and Iran have both a lot to gain and a lot to lose – they certainly do not want the wrong party to win, or they may find new enemies at their doorstep.

With the international community apparently incapable, or unwilling, to act, Saudi-Arabia went as far as deploying ground troops in Yemen. Creating strong, pro-Saudi client states would be an ideal outcome; for the time being, however, it would be enough for Saudi policy makers to prevent Iran from doing so.

New kid on the bloc

With the negotiations on the Iranian nuclear programme progressing greatly, Iran is close to shaking of its international isolation since the Iranian revolution over three decades ago. This could mark the beginning of a new age – Iraq gone and a nuclear deal would negate two important parts in Saudi-Arabia’s attempt to contain Iranian influence in the region.

Iranian client states, from Iraq to Lebanon, granting it access to the Mediterranean Sea, and foreign investment in the Iranian oil industry would grant Teheran both political and economic power. Thus, Riyadh is facing a similar problem as Israel – a new emerging regional power is challenging their policy, and pre-emptive strikes are necessary to prevent the worst.

Kenneth Waltz defined the concept of power equilibriums in international relations: In his realist theory, a balance of power maintains stability. This was, more or less, the case in the Middle East for a long time. But the coming is probably better described with John Mearsheimer’s offensive neorealism – the rise of a new regional power challenges existing regional powers, thus forcing them to act quickly while they are still dominant to prevent the rising power from becoming hegemonic. Looking at Saudi-Arabia’s population of 30 million, its well maintained diplomatic network and its well developed oil industry compared to Iran’s 75 million people, international isolation and its underdeveloped oil industry, it is easy to see how Iran has much more room for improvements, while Saudi-Arabia might be at its peak of power. Better use it before the balance shifts to Teheran’s favour.

This is why Saudi-Arabia is committing to Yemen. This is why it is building coalitions at every possible moment even when they might seem ineffective – coalitions against ISIS and coalitions in Yemen not only help preserve Saudi influence in those countries, but also assure it of support amongst Muslim states. Support, that help reassure Saudi leaders that they can rely on non-Western allies in containing Iran.

One thought on “The Saudi Dilemma”