When rocks become a matter of national security

The Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, including five uninhabited islands and three rocks, each smaller than 3.5 km² (Shaw 1999, 9), have caused diplomatic tensions between China and Japan for the last four decades. Most recently, an increase in Chinese vessels approaching the islands (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2015), currently under Japanese control, as well as an increase in intercepted chinese aircrafts in the area (Japanese MoD 2015) have raised concerns about an escalation of the conflict. The declaration of an East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) by China has further caused the US to send B-52 bombers to fly through the zone (Danner 2014), a move accompanied by similar reactions from Japan and South Korea.

How did islands which China described as „economically and strategically insignificant“ in 1990 (Downs and Saunders 1999) and whose ownership was ignored by both sides until the 70s (Shaw 1999) become such a major issue in the relations between the two countries?

The island dispute is one of the most active territorial disputes in the 21st century (Danner 2014). Yet, to assume that „nothing less than a miracle“ would be needed to solve the issue (Shaw 1999, 132) is too much of a stretch – after all, previous rounds of escalation have been solved diplomatically (Downs and Saunders 1999; Fravel 2010; Hagstrom 2012), and some recent signs of de-escalation are promising (The Asahi Shimbun 2015; Uechi and Nanae Kurashige 2015).

This essay aims at describing the historical origin of the island dispute and how actors came to assign it significance. A discussion of the literature on the causes, ranging from interpretations along the lines of economic liberalism to securitization, will provide an insight into the underlying issues. I will critically engage both notions that China, as a growing power, grows more assertive (Danner 2014), and notions that it will not engage in major conflicts with Japan due to its economic interests and defensive strategy (Downs and Saunders 1999; Fravel 2010; Fravel 2008; Koo 2009). I suggest that the existing literature on the conflict failed to predict the most recent tensions, and does not account for a shift in US policy in the pacific region (Clinton 2011). I will then suggest a strategy to limit tensions regarding the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, combining interests concerning security, the resources and legitimacy.

Where the conflict originates

Both China and Japan agree that the islands were formally incorporated into Japan in 1895. While the Japanese side claims that the Senkaku islands were uninhabited terra nullius prior to that, the Chinese side insists that the Ming dynasty took control over the Diaoyu islands and ceded them to Japan after the Shimonoseki Treaty that ended the 1894-5 war between China and Japan (Fravel 2010; Pan 2007; Downs and Saunders 1999). The islands, now administratively united with the Ryokyu islands and Okinawa, were controlled by the United States after World War II as a result of the San Francisco Peace Treaty (Shaw 1999; Fravel 2010).

During this time, the matter gained little attention; the islands were not regarded as important enough for conflict (Shaw 1999). In 1968, the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (UNECAFE) authored a report that indicated major oil and gas deposits in the sea surrounding the islands (Koo 2009; Shaw 1999). Okinawa authorities set up a national marker engraved with the Japanese name for the islands, followed by Taiwanese protesters travelling to the islands and planting a flag that would later be removed (Shaw 1999). In 1970, Taiwan entered a contract with the Gulf Oil Corporation to develop oil, causing further tensions with Japan (Koo 2009). Similarly, the PRC would make claims on the islands, announcing that exploitation of the area would not be tolerated (Fravel 2010; Koo 2009). International pressure was high on both Taiwan, which was facing the threat of diplomatic isolation in the face of the PRC’s recognition, and the PRC, which was about to gain international recognition (Shaw 1999). In 1972, the Okinawa Reversion Agreement restored Japanese control over Okinawa and the Ryokyu islands, as well as the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands (Fravel 2010; Shaw 1999). Ever since, the islands have been administered by Japan.

The conflict gained attention again in 1978, during negotiations between Japan and China on the Treaty of Peace and Friendship. This treaty, being pushed by China, while Japan was more cautious, aimed at balancing out the Soviet Union – its anti-hegemony clause especially caused scepticism amongst Japanese politicians who did not want to directly oppose the SU (Tretiak 1978). Politicians from the right wing of the ruling LDP offered a compromise: They would support the Treaty, but only if the island dispute would be tied to it, hoping that China needed the anti-hegemony clause more than it needed the islands (Koo 2009; Tretiak 1978). Instead of solving the dispute, this stopped the Treaty talks (Koo 2009). Instead, the Chinese government sent 80 – 100 fishing trawlers with chinese flags to the islands, to show it held on to their claims (Koo 2009; Shaw 1999; Tretiak 1978). About half of these ships were armed, some with machine guns (Tretiak 1978). This reaction was driven by the notion that China’s leaders had been embarassed by Japan’s announcement, as well as domestic pressure and an inter-elite struggle over reforms (Tretiak 1978; Deans 2000). Both sides quickly tried to de-escalate, speaking of accidents and misunderstandings (Downs and Saunders 1999; Tretiak 1978), allowing the Treaty to be signed later that year (Shaw 1999)

The next crisis occured in 1990, when rightwing group Nihon Seinensha applied for a lighthouse, constructed and maintained by them, to become official (Koo 2009; Shaw 1999). This caused a Taiwanese visit to the islands, intending to carry the Olympic torch in a symbolic showcase of sovereignty (Shaw 1999). When the ship was intercepted by the Japanese coast guard, and prevented from entering the islands, coverage of this caused a public uproar in Taiwan and mainland China. In the PRC, however, these protests were suppressed (Shaw 1999; Downs and Saunders 1999). China was careful to calm down activists and reports, minimizing significance of the dispute domestically and trying to prevent anti-Japanese demonstrations (Downs and Saunders 1999). A result of this is that most activists trying to reach the islands have been from Taiwan and Hong Kong (Fravel 2010). Yet, internationally, it supported Taiwan’s claims on the islands, putting pressure on Japan to be more cautious on the issue (Shaw 1999).

Meanwhile, both China and Japan had negotiated the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and signed it in 1982. The Treaty, greatly expanding control over maritime territory, came into power in 1994 (Koo 2009) and was interpreted very differently by China and Japan. First of all, as UNCLOS grants control over seas in an area of 200 nautical miles from the coast or qualified islands, but the distance between China and Japan is only 360 miles, there is an overlap in the claimed territories of the East Chinese Sea (Pan 2007). In the case of such overlaps, UNCLOS suggests compromises between countries. Japan suggests the equidistance principle (i.e. defining a line of equal distance to both countries), while China upholds the natural prolongation principle (i.e. using natural formations as a demarcation line) (Pan 2007). Of course, either side uses a definition most convenient to their own interest. Yet, the possibility of using coasts/islands to increase your Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), allowing for fishing and mining rights, further fuels the island debate (Shaw 1999; Fravel 2010). The original conflict, affecting a sea area 160,000 km² wide (Fravel 2010), is increased by another 40,000 km² of disputed territory (Pan 2007) depending on who owns the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. This also tied to other issues, such as whether Okitonorishima should, as the Japanese name implies, be considered an island and allow claims of an EEZ, or whether it is rather a rock without an EEZ, as China instists (Fravel 2010).

The discussion on EEZs played into the events of 1996, when the infamous Nihon Seinensha built yet another lighthouse on the islands and applied for official recognition. Instead of calming China’s concerns, Tokyo declared the island’s EEZ to be part of Japan (Koo 2009). Additionally, Foreign Minister Ikeda denied the existence of a dispute, as the islands „have always been Japan’s territory“ (Downs and Saunders 1999). This caused serious reactions from the Chinese side, criticising the statement and allowing for more negative press on the issue (Koo 2009). An escalation occured when, after various attempts by activists from Taiwan and Hong Kong to reach the islands and raise Chinese/Taiwanese flags, Hong Kong activist David Chan drowned near the islands (Shaw 1999; Downs and Saunders 1999). This caused massive anti-Japanese protests, which in turn made both governments realize the potential for instability, forcing them to action (Downs and Saunders 1999; Shaw 1999; Koo 2009). By the end of 1997, they had restored relations and signed a fishing agreement solving some of the issues surrounding the island dispute (Shaw 1999).

While most activists attempting to reach the islands had been from Taiwan and Hong Kong (Fravel 2010), the 21st century brought a change in that regard. In 2002, Japan leased the islands from private individuals that had owned them before in order to improve control over activists (Fravel 2010). Yet, instead of calming down the dispute, this drew criticism from China and escalated when chinese activists from the mainland entered the islands in 2004, only to be detained by Japanese authorities (Danner 2014; Koo 2009). Both sides protested sharply: Japan about the activists, China about their detention. Additionally, the opening of the Chinese society resulted in more anti-Japanese protests as a result to the detention (Koo 2009). Both sides tried to de-escalate; in 2005, Japanese authorities raided the offices of the nationalist Seinensha group, while four members of the „China Federation for Defending the Diaoyu Islands“ were placed under house arrest in 2007 (Fravel 2010).

China’s economic growth and need for resources also lead to initial exploration of gas fields, drawing sharp criticism of Japan. While both sides eventually opened negotiations, neither seemed willing to compromise on the issue (Koo 2009; Danner 2014), and it took another four years to sign the Joint Gas Development Agreement (Hagstrom 2012; Wiegand 2009). The Agreement was frozen after Chinese trawler Minjiyu 5179 collided with Japanese patrol vessel Yonakuni, with the captain being arrested and released within the same month (Hagstrom 2012; Danner 2014). As it had done before (Fravel 2010), the US administration acted as a deterrent force by claiming that the Senkaku islands fall unter the Mutual Security Agreement with Japan (Hagstrom 2012; Danner 2014). While the US continues to not take a stance on the sovereignty issue (Shaw 1999; Fravel 2010; Danner 2014; Hagstrom 2012; Koo 2009), the repeated need for the US to stress this point indicates a new level of intensity. While the dispute seemed to de-escalate afterwards, in 2012, Japanese nationalists planned on buying the islands. This sparked new protests by activists who tried to travel from Hong Kong to the islands. As a reaction, the Japanese state bought the islands before the activists could, resulting in new conflict with the Chinese side (Danner 2014). In this scenario, the Chinese government was under pressure from Social Movements to harden its stance. The anti-Japanese protests in 2012 exemplify this. A new low in relations was reached in 2013, when China created an Air Defense Identification Zone, causing the US to announce it would not acknowledge it and resulting in violations of the zone by American B-52 bombers as well as Japanese and South Korean planes (Danner 2014).

The situation improved since November 2014, when a bilateral summit initiated talks (Uechi and Nanae Kurashige 2015). Two months later, both sides resumed talks on an emergency hotline used to prevent conflict escalation after they had been paused in June 2012 due to the islands dispute (The Asahi Shimbun 2015). In March 2015, China and Japan agreed to avoid provocations and to resume political exchanges (Uechi and Nanae Kurashige 2015).

While these develoments indicate an improvement, scramblings of Chinese aircrafts by the Japanese Airforce remain high, and Chinese vessels continue to ship near the islands (see: Chart 1 & Chart 2). Furthermore, the Japanese government has issued new schoolbooks depicting the government’s views on territorial disputes (Takahama 2015). China, meanwhile, remains wary of an update of the bilateral defense cooperation guidelines between Japan and the US that might include the islands (Xinhua 2015).

Explaining behaviour

Fravel identifies three different strategies when dealing with territorial disputes: Delaying, in order to wait for an improved bargaining position while maintaining the claim through public declaration, escalation through the use/threat of force to gain territory, or cooperation, where the actor offers some form of compromise. Escalation is unpredictable, but produces immediate outcomes; Cooperation bears high domestic, but low international costs; and delaying is low cost, but produces no immediate gains (Fravel 2005). China’s „shelving“ of the islands conflict (Shaw 1999) can be regarded as a delaying strategy. Delaying is beneficial to both sides: Japan consolidates its power through the status quo bias of the international law, while China gains time to improve its position (Fravel 2010). Fravel further identifies limits to this delaying strategy. In other cases where the adversary has improved its bargaining position by holding onto land or increasing its military capabilities, China was more likely to escalate the conflict, which corresponds to the preventive war theory (Fravel 2008). The kind of reaction such a perceived shift in bargaining position provokes is further affected by the assigned „value“ of the territory in question (Fravel 2008; Fravel 2005).

Most conflicts around the islands were started by or intensified by activists with no or little governmental association. Limiting their impact might have been the reasoning behind the Japanese government’s purchase of the islands. Either way, the actions of private individuals and social movements remain an important factor in the islands dispute. For example, protests against Japan in China and vice versa were not state-sponsored nationalism, but rather an elite struggle used by the opposition to embarass the ruling party (Deans 2000; Downs and Saunders 1999). Chinese nationalism, based on a history of victimization and loss of territory to both Japan and colonial powers (Downs and Saunders 1999; Fravel 2010), stressed the iportance of sovereignty and territorial integrity, especially against a Japanese „other“ (Downs and Saunders 1999).

Using the concept of securitization, we can further explain the importance on non-state actors: Securitization, i.e. the process of turning something into an issue of security, is the outcome of social processes. Since security, in this understanding, is not only a military/territorial issue, but also linked to legitimacy and identity (Williams 2003), the process of discussing the islands dispute includes societal actors directly. Parts of the population, even when not directly involved in actions concerning the other country, are active in securitizing the issue through discourse and pressure on the governments (Danner 2014). While the Chinese government has used nationalism to replace communist ideology, and both sides use it to maintain legitimacy (Downs and Saunders 1999; Deans 2000), they are in a tricky place, trying to accomodate both nationalists domestically and their economic international interests. Down and Saunders identify three obstacles to nationalism: The state’s capability to satisfy demands, i.e. take control of territory, the international reactions to nationalist policies, and the danger of resulting economic problems creating instability. They conclude that China is likely to use nationalism as a source of legitimacy when the economy is doing poorly, but using economic legitimacy when it is booming. They also find that both Japanese and Chinese leaders have pursued economic interests rather than nationalist ones (Downs and Saunders 1999), something putting them under pressure by the same nationalists they were using for legitimacy before. Thus, we can expect economic interdependence to de-escalate conflict (Koo 2009) – yet, despite growing economic interdependence, the conflict continues. A reason for that could be China’s issue linkage/coercive diplomacy strategy: By tying the islands dispute to other issues, it can enforce Japanese behaviour, affecting economic aid, Japan-US security agreements and Japanese troop deployments, to name but few (Wiegand 2009).

Another question raised when it comes to predicting behaviour in the dispute is whether China is acting from a position of strength or weakness. While recent events indicate a more assertive behaviour of China (Danner 2014), a closer comparison to other crisis imply that Japan was acting more assertively in 2008, while China was remaining consistent in its behaviour. Indeed, the strengthened US commitment to defend the islands in 2010 increased support for the US Futenma base on Okinawa, and the increase in Japanese defense capabilities and diplomatic repercussions for China indicate that Japan’s position was improving rather then deteriorating (Hagstrom 2012). Fitting Fravel’s point that a change in bargaining power will result in a Chinese reaction (Fravel 2010), we have seen a new escalation of the conflict in 2012, resulting in yet more US commitment the following year (Danner 2014).

Making sense of the dispute

Studies of the islands dispute encounter a problem familiar to International Relations scholars: The samples are very small. Fravel compares different border disputes, which is problematic: Mashing together conflicts concerning large land borders with separate islands, and conflicts from before the 70s with a conflict that only gained prominence afterwards (Fravel 2008; Fravel 2005), makes results less conclusive. This is why he looks at the islands conflict separately (Fravel 2010); but that way, it is hard to account for changes in the international environment. While he does observe a possible shift in Chinese policy since government ships entered waters near the islands, he assumes that delaying will continue, and compromises will not occur until they will be more urgent, for example due to resource hunger (Fravel 2010).

A more conclusive approach is that of Wiegand, using conflicts that occured around the islands dispute and comparing whether they were linked to other issues or not. She finds that the territorial dispute is part of both countries’ general competition for dominance in Asia (Wiegand 2009). Meanwhile, we see fewer activities by non-state actors: The fishing boats exploring the sea near the islands seem to be increasingly state-sponsored (Fravel 2010), and the purchase of the islands by the government was intended to limit activist’s impact (Danner 2014). Thus, inter-elite conflict (Deans 2000) grows less helpful.

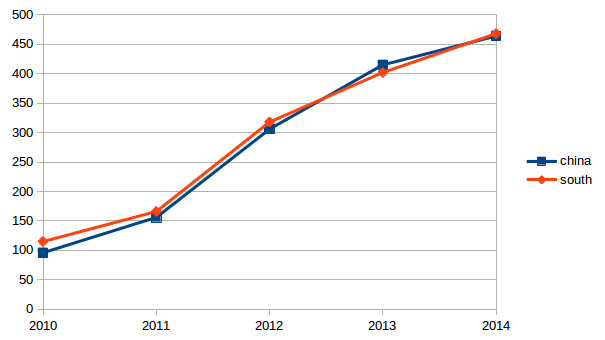

Neither of these approaches alone explain the escalation that occured since 2012. Hagstrom’s argument that Japanese assertiveness caused conflict (Hagstrom 2012) is more in line with both Fravels argument and the data: The number of Chinese aircrafts scrambled by Japan and the number of aircrafts scrambled by Japan in its south increased 2010 – 2014 (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Number of aircrafts scrambled by Japan

(Japanese MoD 2015)

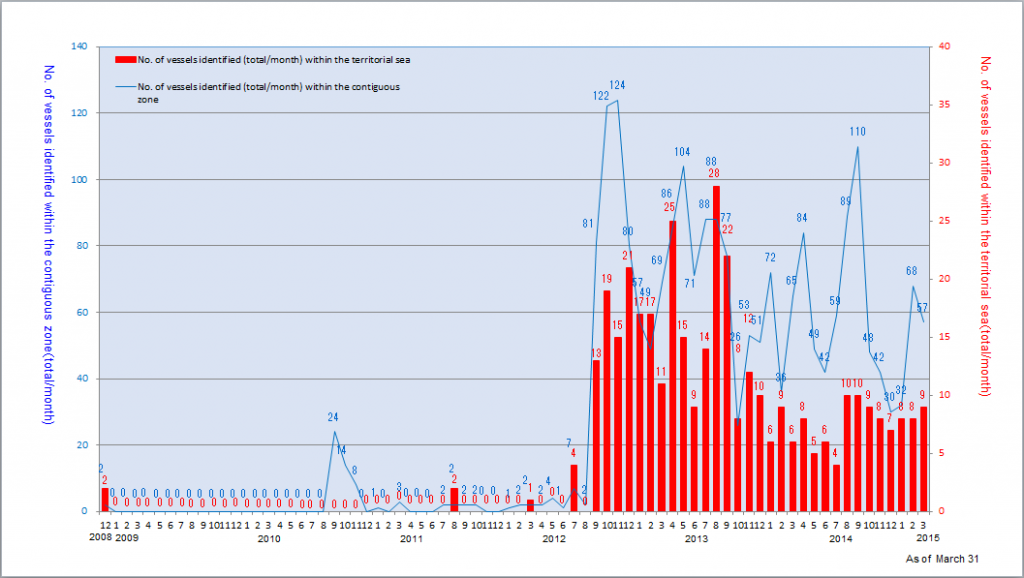

Meanwhile, more and more vessels were stopped by Japan near the islands (Chart 2). The increase started around the time Japan purchased the islands from private individuals. It also corresponds to renewed efforts by both Japan and the US to increase their presence in the Pacific. It is what former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton dubbed a „pivot“, announcing to focus more on security and the economy in Asia (Clinton 2011). The US, after trying not to comment on the sovereignty issue, has increased its cooperation with Japan recently. First, by stressing that the Mutual Security Agreement covers the disputed islands (Fravel 2010), then by demonstratively ignoring the Chinese ADIZ in cooperation with Japan and South Korea (Danner 2014). Newer examples include the update of the bilateral defense guideline, which is carefully followed by China (Xinhua 2015). Meanwhile, Japan has tightened its defenses, including possible changes to the constitution to allow deployment of forces abroad, building a helicopter-carrier and improving its airforce. This is accomoanied by the US moving marines to Australia and announcing to send warships to Japan (Sengupta 2014).

This shift in US/Japanese strategy is likely to raise concerns in China. Unlike previous conflicts, where China supressed media coverage (Downs and Saunders 1999), China’s state owned news corporation Xinhua published 15 articles on their english homepage during the last month1. An increase in bargaining power by its adversary is supposed to create a pre-emptive strike by China (Fravel 2010); but in the case of the islands, its capabilities are limited. Taking the islands by force will provoke the US, an unlikely fight for China. Instead, the increase in vessel incidents could be what Wiegand describes as issue linkage: trying to prevent further US/Japanese activities by implicitly offering to stop sending vessels near the islands.

Chart 2: Number of vessels „intruding“ area around islands

(Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2015)

With this analytical framework, we can then assume that more caution in US-Japanese relations will help to reduce conflict with China. Anything changing the status quo will be considered an aggressive act by China; including China in regional talks should be part of the US’ strategy, rather than building an anti-Chinese alliance (or seem to be doing so).

As territorial conflicts concern „the interpretation of the historical background and the legal context of a piece of Territory“ (Hagstrom 2012, 270), careful wording is required. Japan denying the existence of a conflict publicly is likely to increase tensions. Paying attention to the nationalist pressure on both the Chinese and Japanese governments (Downs and Saunders 1999; Danner 2014) helps assess their diplomatic flexibility. Economic issues, such as gas field development, is likely to have a positive impact on Japanese-Chinese relations if both have an equal need for the resources; as of now, it seems like Japan is more eager to develop them (Fravel 2010).

Conclusion

The Senkaku/Diaoyu islands dispute has historical roots that go back to the Chinese-Japanese war in 1894-5. They involve a mix of nationalist sentiment, securitization dynamics, regime legitimacy and economic and strategic interests (Downs and Saunders 1999; Danner 2014; Deans 2000; Fravel 2010; Pan 2007). While economic interdependence is supposed to reduce conflict, it failed to do so with the recent escalation since 2012 (Downs and Saunders 1999; Koo 2009; Danner 2014). Instead, we saw an increasing presence of China, Japan, and even the US (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2015; Japanese MoD 2015; Sengupta 2014; Clinton 2011).

This can be explained by two mechanics central to Chinese diplomacy: Delaying until the adversary tries to change the bargaining position or its own bargaining position improves (Fravel 2005; Fravel 2008), and linking the islands dispute to other, more urgent issues to achieve policy goals (Wiegand 2009). The bargaining position was changed by a shift in US policy and increased presence in the Pacific (Clinton 2011; Sengupta 2014). By increasing conflict over the islands, then, China may hope to affect bilateral cooperation between Japan and the US like the currently ongoing negotiations in April 2015 (Xinhua 2015).

Solving the conflict might seem like a „miracle“ (Shaw 1999, 132), but resolving the current crisis is possible if both the US and Japan accomodate Chinese interests in their policy shifts. Short term, they should refrain from military redeployments that could alienate China and cause it to increase conflict over the islands. Long term, exploring common economic interests in the development of gas and oil fields might prove promising and further reduce tension. Since the issue is linked to legitimacy issues concerning nationalism (Downs and Saunders 1999; Deans 2000), de-securitizing it on a societal level would be necessary in order to solve the dispute. Reframing it in discourse as an issue of cooperation rather than nationalist confrontation is necessary to consequently end the dispute (Danner 2014) – yet, this is a highly unlikely scenario. A continued delaying (Shaw 1999; Fravel 2010), rather than military escalation seems like the best case scenario.

Bibliography

Clinton, Hillary. 2011. “America’s Pacific Century.” Foreign Policy. http://www.us-global-trade.com/Hilary Clinton.Asia (Foreign Policy Nov. 2011).pdf.

Danner, Lukas K. 2014. “Securitization and De-Securitization in the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands Territorial Dispute.” Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social …. http://www.japss.org/upload/4. Danner.pdf.

Deans, Phil. 2000. “Contending Nationalisms and the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Dispute.” Security Dialogue 31 (1): 119–31. doi:10.1177/0967010600031001010.

Downs, Erica Strecker, and Phillip C. Saunders. 1999. “Legitimacy and the Limits of Nationalism: China and the Diaoyu Islands.” International Security 23 (3). MIT Press 238 Main St., Suite 500, Cambridge, MA 02142-1046 USA journals-info@mit.edu: 114–46. doi:10.1162/isec.23.3.114.

Fravel, M. Taylor. 2005. “Regime Insecurity and International Cooperation: Explaining China’s Compromises in Territorial Disputes.” International Security 30 (2). MIT Press 238 Main St., Suite 500, Cambridge, MA 02142-1046 USA journals-info@mit.edu: 46–83. doi:10.1162/016228805775124534.

———. 2008. “Power Shifts and Escalation: Explaining China’s Use of Force in Territorial Disputes.” http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/isec.2008.32.3.44.

———. 2010. “Explaining Stability in the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands Dispute.” Getting the Triangle Straight: Managing China–Japan– …. http://www.jcie.org/researchpdfs/Triangle/7_fravel.pdf.

Hagstrom, Linus. 2012. “‘Power Shift’ in East Asia? A Critical Reappraisal of Narratives on the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands Incident in 2010.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 5 (3): 267–97. doi:10.1093/cjip/pos011.

Japanese MoD. 2015. 平 成 2 6 年 度 の 緊 急 発 進 実 施 状 況 に つ い て. http://www.mod.go.jp/js/Press/press2015/press_pdf/p20150415_01.pdf.

Koo, Min Gyo. 2009. “The Senkaku/Diaoyu Dispute and Sino-Japanese Political-Economic Relations: Cold Politics and Hot Economics?,” June. Taylor & Francis Group. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09512740902815342#.VTP8wOSli1E.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 2015. “Trends in Chinese Government and Other Vessels in the Waters Surrounding the Senkaku Islands, and Japan’s Response.” http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/page23e_000021.html.

Pan, Zhongqi. 2007. “Sino-Japanese Dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: The Pending Controversy from the Chinese Perspective.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 12 (1): 71–92. doi:10.1007/s11366-007-9002-6.

Sengupta, Kim. 2014. “As China Decries Japan’s Rising ‘Voldemort’, the UK Remains Quiet.” Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/as-china-decries-japans-rising-voldemort-the-uk-remains-quiet-9056888.html.

Shaw, Han-yi. 1999. “The Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands Dispute: Its History and an Analysis of the Ownership Claims of the P.R.C., R.O.C., and Japan.” Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies. http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mscas/vol1999/iss3/1.

Takahama, Yukihito. 2015. “Government Stance on History, Isles Spelled out in Textbooks.” The Asahi Shimbun, April 7. http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/politics/AJ201504070081.

The Asahi Shimbun. 2015. “Japan, China Resume Talks on Emergency Hotline after Long Hiatus.” The Asahi Shimbun. http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/politics/AJ201501130058.

Tretiak, Daniel. 1978. “The Sino-Japanese Treaty of 1978: The Senkaku Incident Prelude.” Asian Survey. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2643610.

Uechi, Kazuki, and Nanae Kurashige. 2015. “Japan, China Agree to Avoid Provocations, Resume Political Exchanges.” The Asahi Shimbun. http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/politics/AJ201503240070.

Wiegand, Krista E. 2009. “China’s Strategy in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands Dispute: Issue Linkage and Coercive Diplomacy.” Asian Security 5 (2). Taylor & Francis Group: 170–93. doi:10.1080/14799850902886617.

Williams, Michael C. 2003. “Words, Images, Enemies: Securitization and International Politics.” International Studies Quarterly 47 (4): 511–31. doi:10.1046/j.0020-8833.2003.00277.x.

Xinhua. 2015. “China Voice: Japan, U.S. Shouldn’t Drag Diaoyu Islands into Bilateral Defense Guidelines,” April 16. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-04/16/c_134157874.htm.